Employees often present themselves with job titles on LinkedIn profiles, business cards, email signatures, or other external-facing channels that may differ from their official titles in the company’s HR system. These self-assigned or “vanity” titles can range from minor tweaks (e.g. calling oneself “Senior Analyst” instead of “Analyst II”) to creative embellishments (like “Guru” or “Ninja”) to outright inflation (“Director” instead of “Manager”). While internal HRIS titles are usually managed and governed by the organization’s career hierarchy, external-facing titles often slip through formal oversight.

This article examines the legal and organizational risks tied to such external titles, contrasts them with internal titles, and discusses how companies might govern this practice. It balances fact-based legal analysis with real-world HR and Compensation expert opinions on best practices.

Internal Titles vs. External “Vanity” or “Position Titles”

Internal job titles (those in the HRIS and official records) are the formal designations HR and management assign to a role. These titles typically link to a job description, pay grade, and employment classification. Internal titles are used to create clear career pathing, identify internally equitable roles, and clearly outline thee job’s responsibilities. In contrast, external-facing titles are how an employee chooses to represent their role to the outside world. These might appear on LinkedIn, resumes, business cards, or email signatures, and employees sometimes tweak them for better external understanding or personal branding. For example, an internal title “Software Engineer II” might be presented externally as “Senior iOS Developer” for a clearer description of the role to clients or recruiters.

The key difference in external titles and position titles is control and audience: internal titles are company-controlled for internal purposes, whereas external titles are often employee-driven and aimed at an outside audience. This divergence can create misalignment – an employee’s external title might not match their actual responsibilities or level, which can lead to confusion both inside and outside the organization. But, the question arises: “How important is it that unofficial titles are managed and who should manage them?”

Key Legal Risks of Self-Assumed Titles

When employees invent or inflate their own job titles externally, some legal risks may be introduced. Potential risks include misrepresentation and fraud, issues of apparent authority in contract law, regulatory compliance problems (especially with titles that imply a license or certification), and even complications in wage and hour classifications. Below we explore each of these legal risk areas in the U.S. context.

Misrepresentation and Apparent Authority

From a legal standpoint, one major concern is that an inaccurate external title could constitute a form of misrepresentation – intentionally or not – to third parties. If an employee overstates their position or authority, clients or partners might rely on that title to make decisions. In law, this ties into the doctrine of apparent authority, where a company can be held bound by an employee’s actions if the company has “clothed” that employee with an appearance of authority. For example, imagine a lower-level employee whose official title is “Assistant Sales Representative” but who labels himself “Sales Director” on LinkedIn. If he signs a contract with a customer under the “Director” title, the customer could reasonably assume he has the authority to do so. Under apparent authority principles, the company might find itself legally obligated or embroiled in a dispute, even if the employee exceeded his actual authority. In essence, by failing to correct or prevent the misuse of titles, the company may be deemed to have permitted the misrepresentation.

It’s worth noting that courts look at whether the third party’s belief in the agent’s authority was reasonable. An expert in employment law warns that allowing employees to present inflated titles can “give a false sense of authority to outsiders, potentially binding the company to deals or representations it never authorized” (expert opinion). In practice, this means organizations should be wary of employees calling themselves “Head of [X]” or “VP” if they are not – these titles carry weight. As one legal advisor puts it, it is ultimately the company’s responsibility to ensure others aren’t misled by an employee’s title, either by clearly communicating actual roles or by intervening when an employee’s external title is inappropriate.

Beyond contracts, misrepresentation via title could also lead to fraud or liability issues. If an employee falsely presents as a licensed professional (e.g., an “Engineer” or “CPA” when they are not) or as an officer of the company, and a third party is harmed by relying on that, lawsuits could follow. At a minimum, a misleading title can damage the trust of third parties. Companies have an interest in preventing employees from overselling their position or credentials to avoid both legal entanglements and reputational damage.

Regulatory and Licensing Compliance

Another risk area involves regulated titles – job titles or designations that are restricted by law to individuals with specific credentials or licenses. In the U.S., many states have laws protecting titles like “Engineer,” “Certified Public Accountant (CPA),” “Architect,” “Attorney,” “Medical Doctor,” etc. Using such titles without the requisite license can violate state licensing laws or professional regulations. For instance, Texas law explicitly prohibits anyone who isn’t a state-licensed engineer from “being represented in any way as any kind of ‘engineer’” or making any professional use of the term “engineer.” Thus, if a building developer in Texas (who is not a licensed Professional Engineer) whimsically lists their title as “Construction Engineer” on LinkedIn or a business card, they (and by extension their employer) could face scrutiny or penalties from the state engineering board.

Similar concerns apply to other licensed titles: an employee calling themselves “Financial Advisor” or “Investment Consultant” might trigger FINRA/SEC regulatory definitions; someone calling themselves “CPA” without a license is unlawfully holding out as a certified accountant; a non-lawyer using “Esq.” or “Attorney” could be seen as unauthorized practice of law. Even terms like “VP” or “Director” can be regulated in specific industries (for example, banking regulators pay attention to who is listed as a company officer).

Regulatory compliance, therefore, requires companies to monitor the titles that employees publicly adopt. At a minimum, organizations should prohibit employees from using titles that imply licensure or credentials they do not actually hold. This protects both the employee from personal legal liability and the company from fines or public embarrassment. It also aligns with professional ethics, ensuring the public isn’t misled about who is qualified to perform certain work.

Governance: Who Should Manage External Titles?

Given the above risks, a completely laissez-faire approach (letting employees call themselves whatever they want externally) is not ideal. But whose job should it be to govern or approve these external-facing titles? Opinions in the professional community differ. Some argue for HR oversight, others for Compensation/Total Rewards teams, some say line managers should decide, and a minority feel no one should police external titles (trust employees or handle issues case-by-case).

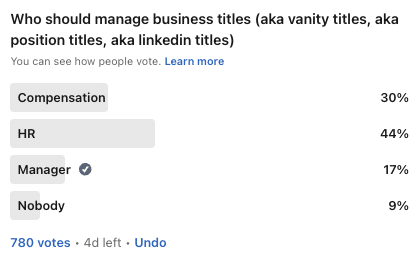

Figure: Poll results from a LinkedIn survey (780 votes at the time of this article) asking “Who should manage business titles (aka vanity titles, aka LinkedIn titles)?” The majority (44%) answered HR, 30% chose Compensation, 17% Manager, and 9% Nobody (no formal governance).

The poll results show a strong preference for HR ownership of the issue, with Compensation and managers as alternate choices. Let’s examine the rationale and pros/cons of each approach, incorporating expert commentary:

Human Resources Should Manage External Titles (44%)

Nearly half of the participants in the poll agree that the HR team should be responsible for managing externally facing titles.

- Pros: HR is typically responsible for maintaining job architecture and compliance, so it is well-positioned to ensure external titles don’t pose legal risks or internal equity issues. HR can provide a centralized, consistent policy and prevent abuses (e.g., no one calls themselves “CEO” unless they are). Additionally, the HR team’s purview is employee-facing interactions, so they are well-suited for such compliance measures.

- Cons: If HR tightly controls every external title, it may become bureaucratic and slow. HR may also be somewhat removed from the day-to-day nuances of each role, so there’s a risk of them enforcing overly generic titles that don’t resonate externally. An HR leader in favor of governance noted that “consistency is key – HR oversight ensures no one inadvertently creates a liability or PR fiasco with a wild title” (expert opinion). On the other hand, some employees and managers fear HR control could stifle legitimate personal branding.

Compensation Should Manage External Titles (30%)

- Pros: The Compensation/Total Rewards team usually manages internal leveling and titles for pay purposes, so they have deep insight into role seniority. Additionally, many compensation teams are responsible for the development and implementation of the career framework and job hierarchy. If the comp team also manages external titles, they can align them with internal grades (for example, only employees in a certain pay grade can call themselves “Senior” or “Director”). This can preserve internal equity and prevent title inflation from getting out of hand.

- Cons: Compensation professionals might not be best suited for policing LinkedIn or email signatures since their focus is usually internal equity and market pay, not external branding. Compensation and Total Rewards teams do not usually engage in employee-facing compliance issues in the way that HR partners may. One compensation expert commented that “while linking external titles to our internal leveling makes sense for fairness, it can be overkill to have Comp approve every business card – guidelines might suffice” (expert opinion). This suggests a middle ground: comp sets the framework (what titles correspond to which levels), and HR or managers implement it.

Managers Should Manage External Titles (17%)

- Pros: The employee’s direct manager knows their job best. Managers can decide how their team members present themselves externally in a way that is accurate and beneficial to the business, as well as in line with industry standards, which they may be more familiar with than other members of the business. This decentralized approach can be more flexible and responsive to industry norms (e.g., a marketing manager might allow a “Social Media Strategist” title because that’s understood in the field, even if internally the person is “Marketing Associate”). With the right guidelines in place, the management of external titles by managers can ensure industry relevant titling while maintaining relative compliance.

- Cons: Without oversight, different managers may apply different standards, leading to inconsistency across the company. One team might have extravagant titles while another is conservative, causing fairness issues. Also, individual managers might not be versed in legal risks – a well-meaning manager could approve a risky title not realizing the implications. An HR expert cautions that “leaving it to managers invites inconsistency; one manager’s ‘VP’ is another’s ‘Lead,’ which can create internal confusion and external misalignment” (expert opinion). Still, some organizations use manager approval effectively, within a broad policy framework.

Nobody Should Manage External Titles (9%) –

Pros: This view holds that external titles are a personal matter and policing them is overkill. Trusting employees to manage their own personal brand can boost morale and avoid the “title police” feeling. It also reduces administrative overhead – HR/Comp can focus on internal matters and only intervene if a problem arises. Startups and flat organizations often adopt this laissez-faire approach, allowing creative titles or flexible self-description.

Cons: As we’ve explored, a lack of title governance means high risk of misrepresentation, inconsistent branding, and legal pitfalls slipping through. Most experts warn that completely ignoring external titles is asking for trouble. In the poll, only 9% favored having no one in charge, reflecting the general consensus that some level of oversight or guidelines are necessary. Even those who dislike strict rules often agree that companies should at least publish guidelines about unacceptable titles (e.g., no false credentials, no profanity, etc.) and encourage employees to run unusual titles by someone for a gut check.

In reality, decisions do not happen in a silo and compliance requires a multi-faceted approach. A combination approach is likely the best outcome. The poll’s outcome and commentary suggest that a balanced governance model is preferred: HR (and/or Comp) provides the guardrails, and managers ensure compliance in their teams. This way, external titles are neither a free-for-all nor a total bureaucratic dictate – employees get some creativity, but within a risk-managed framework.

Best Practices for Managing External Titles

Striking the right balance between employee autonomy in self-presentation and protecting the company’s interests is key. Based on legal considerations and HR best practices, here are some strategies organizations can use:

- Establish a Clear Policy or Guidelines: Companies should craft a policy that defines acceptable external titles and the process for choosing them. This policy might state, for example, that the external title should reflect the person’s actual role and not exceed their internal level or imply authority they don’t have. It should ban any use of licensed/professional titles that the employee isn’t credentialed for. As one recent analysis put it, “Organisations should establish clear guidelines and criteria for assigning job titles to ensure consistency and transparency… aligning job titles with actual responsibilities.” By providing a framework up front, employees know the boundaries.

- Training and Communication: Simply having a policy isn’t enough; companies should educate managers and employees about why it matters. Explain the legal risks (misrepresentation, apparent authority, etc.) and the brand considerations. When people understand why calling oneself “VP of Finance” without approval is problematic, they are more likely to comply. Open communication can also encourage employees to ask if unsure – it creates a culture where people check “Can I use this title externally?” without fear. In the guidelines, encourage consultation: if an employee wants to use a creative title (“Data Wizard”, “Innovation Alchemist”), they should run it by HR or a supervisor first.

- Tie External Titles to Internal Structure: Many companies find it effective to map external-facing titles to internal levels or job codes. For instance, the policy might say: if your official title is X, you may represent it externally as one of Y or Z options. This ensures no junior employee styles themselves as a senior exec. It can be as simple as providing a list (e.g., “Analyst I/II = Analyst or Senior Analyst externally; Manager = Manager or (Area) Lead; Director = Director; VP = Vice President”, etc.). This mapping should be flexible enough to account for industry norms but firm enough to prevent leaps. Such an approach often requires collaboration between HR and Compensation to get the leveling right.

- Monitor and Enforce Selectively: It may not be feasible (or desirable) to actively police every LinkedIn profile, but HR can incorporate external title review at certain points. For example, when someone gets a promotion or during new hire onboarding, you might ask the employee, “How will you represent this role on LinkedIn or otherwise? Let’s make sure it’s appropriate.” If a problematic title comes to light, address it in a one-on-one conversation rather than immediately being punitive. The goal is to correct quietly and educate, not embarrass the employee. In serious cases (e.g., an employee refuses to remove a misleading title), companies should have a procedure to require compliance, since it does affect the business.

- Lead by Example from the Top: Company leadership should also adhere to these standards. If executives start inventing flashy external titles for themselves outside what’s on the org chart, it sets a precedent that others will follow. By the same token, leaders can champion the rationale – e.g., a CTO might tell the engineering team, “I know many of you use ‘Software Engineer’ vs ‘Developer’ interchangeably, but remember in certain states ‘Engineer’ is a licensure term – check our guidelines before posting your title.”

- Regular Review and Update: As industries and roles evolve, title conventions change. HR should periodically review the external titles being used in the company (perhaps through LinkedIn or an internal survey) and update the guidelines accordingly. New risks may emerge (for example, a new certification becomes prevalent and people start adding it to titles without actually having it). A good practice is to make external titles part of the job architecture reviews that Compensation/HR do, to ensure everything stays aligned with reality and law. Remember, the working world is dynamic – your policy should be a living document as well.

By implementing these best practices, organizations can significantly mitigate the risks associated with vanity titles while still allowing employees some flexibility to describe their roles in externally meaningful ways. It’s a classic case of balancing governance with empowerment.

Sources:

- U.S. Department of Labor – Fact Sheet #17A: Job Titles Do Not Determine Exemption Status

- Texas Occupations Code §1001 Engineering Practice Act: Restrictions on use of “Engineer” title

- Fullerton & Knowles, P.C. Authority to Sign: Actual & Apparent: Explanation of apparent authority and importance of not cloaking agents with unintended authority

- LinkedIn Poll (2025): Who should manage business titles?

Professional opinions on governance of external titles

- Pej X. Chen, “Unravelling Job Title Inflation: Navigating Challenges and Solutions”: Consequences of inflated titles linkedin.com and recommendations for guidelines

No responses yet